Photo50 2024: Meet the Curator, Revolv Collective

The theme for Photo50 2024 is Grafting: The Land and the Artist. The exhibition, guest curated by Revolv Collective, explores expanding photographic practice and the subject of labour and its diverse representations within the context of the land. In the exhibition, labour will be contextualised from a variety of positions to question our understanding and engagement with the land as a site of work, resistance, action, co-dependence, regeneration and communion. Echoing the horticultural technique whereby two plants are joined in order to grow together, these artists propose an ethos of entanglement, a space for contemplation and learning about the world, its complex systems and ecologies.

We sat down with Revolv Collective to learn more about the exhibition and what we can expect to see at London Art Fair 2024. Read the interview below and don’t forget to secure your tickets to see the exhibition in person this January.

We’re so excited to welcome Revolv Collective as the curatorial group behind Photo50 2024. Could you please introduce Revolv to our audience in case they aren’t familiar with its work?

We are honoured to have been invited to curate Photo50 2024! Revolv Collective is an artist-run organisation based in the UK that promotes the practice, teaching and dissemination of expanded photography. Lina Ivanova and Krasimira Butseva established Revolv in 2017 in Portsmouth, UK, with the ambition to create opportunities for early-career artists.

Since then, our numerous projects have fostered creativity and artistic innovation through a collaborative, interdisciplinary and non-hierarchical approach focused on access to educational and professional resources. The collective’s active members are Lina Ivanova, Laura Bivolaru, Victoria Doyle, Alexander Mourant and Lucas Gabellini-Fava, with honorary members, Krasimira Butseva and Ibrahim Azab.

The collective’s practice incorporates teaching, curating, and publishing, as well as portfolio reviews, mentorship and peer-to-peer learning.

The curatorial theme you’ve created for Photo50 2024 is Grafting: The Land and the Artist. Could you introduce the concept and what inspired it?

This year, in the process of transitioning from an artist collective to an organisation, we have revisited Revolv’s core values and recognised that the concept of artistic labour is often overlooked in the contemporary discourse on art, and especially in photography, which is dismissed as a less laborious medium.

The curatorial theme emerged from an exploration of the myriad forms that the artist’s labour takes and initially we proposed an ambitious survey of different approaches. We soon realised that a stronger show would be one focused on a specific context, and taking into account the members’ current individual interests and practices, we decided to hone in on the theme of labour within the context of nature and the land.

We took inspiration from the horticultural technique of grafting, which entails joining two plants together for the purpose of repairing one of them, strengthening their resistance to disease, ensuring they adapt to adverse climates or producing multifruited or multiflowered plants. For us, grafting has come to symbolise a union between labour, nature, and artistic expression, but also between different artistic perspectives, which, when brought together, can offer us a more holistic view of art as an integral part of life.

In your curatorial description you mention the “subject of labour and its diverse representations within the context of the land”. What types or forms of labour are being explored in this exhibition?

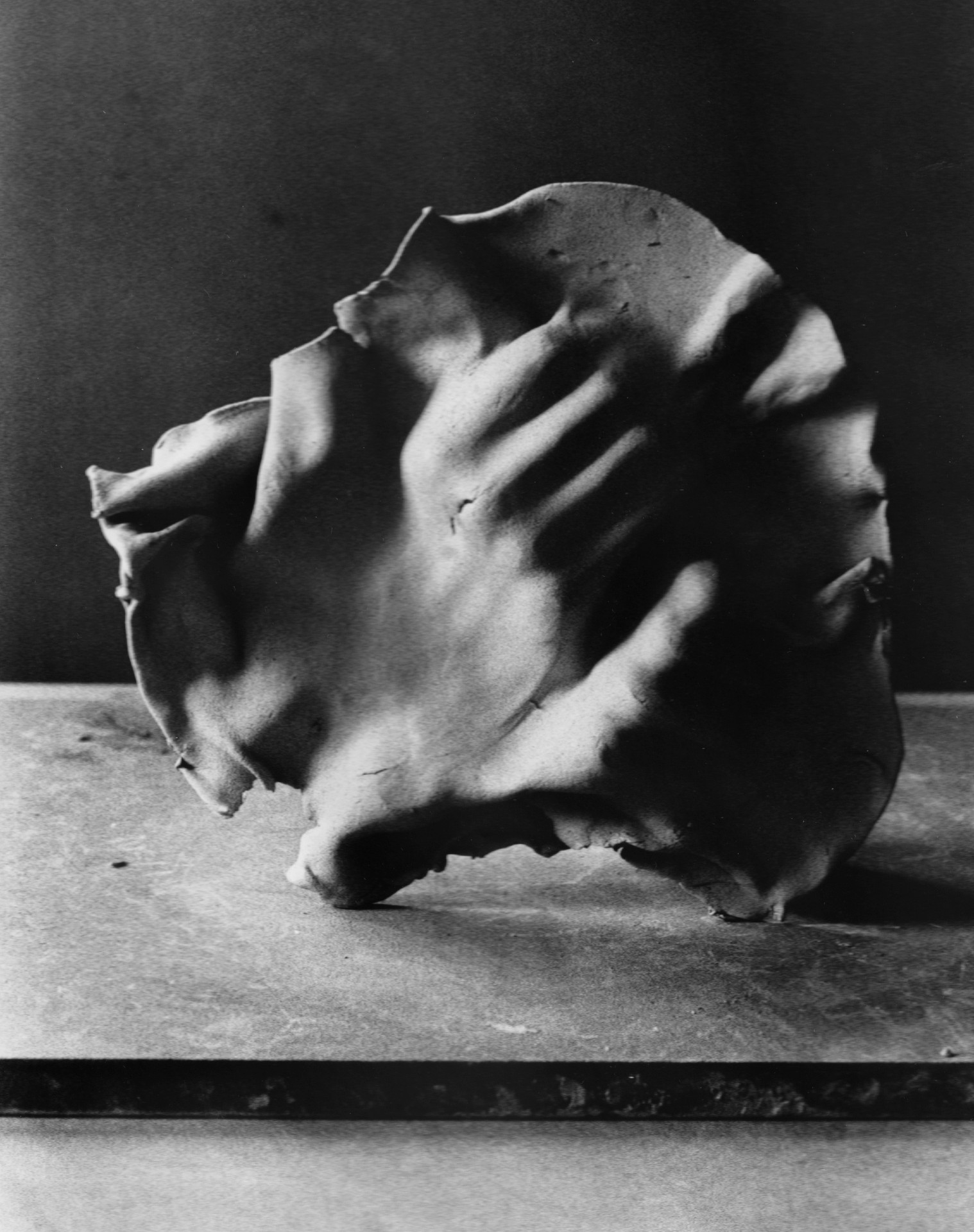

First of all, the exhibition reframes photography as a laborious medium. Photography is often not about pressing a button, but it involves a wide range of techniques, such as developing film or analogue printing, that require the same mastering of skills as painting or sculpture. Many of the exhibited works are the result of physical, manual labour, from Eugénie Shinkle’s Ideal City (Somebody Else’s Landscape), hand-sewn from thousands of contact prints, to Jackson Whitefield’s rubbings of seacoal, burnt gorse and mining waste onto paper.

In addition, artists rarely just take pictures. More often than not, research plays a significant part in the art-making process, with artists developing innovative techniques, like Hannah Fletcher and Alice Cazenave’s sustainable developers and fixers. Their commitment to non-toxic ways of making images also speaks of the labour of care for the environment, something we all, artists or not, have to become more mindful about integrating into our daily lives.

Most of the artists we have discussed and collaborated with over the years cannot really sustain themselves financially purely from their practices, and therefore have to take on other jobs, for example teaching. Arts education is also one of our main interests and we are aware of the amount of physical, intellectual and affective labour it requires. Teaching often feeds and stimulates an artist’s practice, as is the case of exhibiting artist, Joshua Bilton, and we think it would benefit from being considered a part of the process of making work, and not an extraneous activity.

A central motivating factor in this exhibition is the ‘expansion of photographic practice’. Could you expand on this concept and its importance?

Photography’s founding vocabulary can be said to be rooted in colonial extraction. In English we say that a photographer takes a photograph, which entails that the photographer makes a copy of reality, then displaces the likeness from its referent. Many other languages use the equivalent of make for the process of creating a photograph. An expanded photographic practice is rooted in making, not in taking.

The traditional photographer points their camera at the world and takes its likeness, which is then presented pictorially, as a framed print on a wall. We’re not very interested in that, but in the representation strategies artists use today that focus on the freedom of artistic expression, and not on the idiosyncrasies of the medium.

Expanded photography is a bit wild – it’s transdisciplinary, technically imperfect and you won’t find it on the wall very often! It’s also the result of a deeply considered process where perhaps practice is the actual research, or where there is an inherent relationship between the subject of the work and how the image was created or presented. Expanded practitioners are immersed in the artistic process, they prioritise material and technical experimentation and don’t care very much about the dictionary definition of photography. Grafting is at the core of their practices, whether it’s joining mediums or ideas.

What criteria did you employ when selecting artists to participate in this exhibition?

In our curation process, we played the game ‘where’s the labour?’ with every artist we considered, in order to assess the impact the work would have as part of the exhibition. With every artist we considered, in order to assess the impact the work would have as part of the exhibition. We wanted to propose a multifaceted take on labour, so we were looking for diverse and thought-provoking practices.

With every artist who joined, we were noticing how fertile the concept actually is and how differently one can approach it. Each angle is unique, although what all exhibiting artists have in common is a certain care for the land. Contemporary artists are troubled by the climate emergency; even when it’s not tackled directly in their work, it still lurks in the background.

What impact do you hope the exhibition will have on audiences?

On one hand, through the showcased expanded practices, we aim for visitors to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for the diverse labours involved in these artistic endeavours. Moreover, we hope to provide insight into the rich context and extensive research that underpins each artist’s work.

On the other hand, by exploring the entanglement between the artists and the land, the exhibition prompts audiences to contemplate how we, as a society, engage with and inhabit the natural world. The question we are posing is the following – what can we learn from these artists about the land, its millenary knowledge, and its potential for cohabitation, renewal, and regeneration?

In the current age of climate crisis, perhaps we need to steer clear of anthropocentric representations of the landscape and encourage approaches that help us to rethink our position. Humans are exceptional in many ways, but we can’t exist outside our ecosystems.

You’ve said previously that the artists represented in Grafting “propose an ethos of entanglement”. How does this function within the context of artistic production and what does this ethos have to offer the artist and the viewer?

The exhibiting artists don’t just propose an ethos of entanglement, they actively manifest it in their practices, inspiring us to reconsider our relationship with nature and the land.

Take, for example, Jackson Whitefield, who collaborates directly with the landscape by dragging canvas over charcoal fields of burnt gorse and making rubbings in the ground of old quarries and mines. His artwork emerges through a tactile connection with the land, reflecting at the same time on his family history in Cornwall. Another artist in the exhibition, Rahima Gambo, recognises the land as both process and medium, as she gathers various objects during walks, which both inform and appear in her work. At the same time, Rowan Lear mimics the technique of grafting in her work, A Sudden Branching, to emphasise the mingling bodies that make up an ecosystem.

The notion of entanglement also extends to the ways in which artists reconfigure the history of art. Eugénie Shinkle’s Ideal City (Somebody Else’s Landscape) rebuilds sections of four paintings by JMW Turner from her own 35mm contact prints in order to reflect on the alienation experienced by the artist in the English landscape after moving here from Canada. Marie Smith’s cyanotypes borrow the technique pioneered by 19th century English botanist and photographer, Anna Atkins, to meditate on the concept of extraction: what could a conversation between Atkins, whose husband owned slaves in Jamaica, and Smith, who is of Jamaican heritage, look like today through the very medium that established Atkins’ reputation?

Photography as a medium can uniquely represent and document labour in ways that other mediums may struggle to achieve. Artists like Joshua Bilton, who is engaged in social practice, often rely on photography to disseminate their work, highlighting the intricate entanglements between artistic expression, labour, and collaboration with different communities.

The notion of entanglement offers both the artist and the viewer the opportunity to establish a profound connection to the land and the chance to reflect on what a sustainable and meaningful artistic practice can look like.